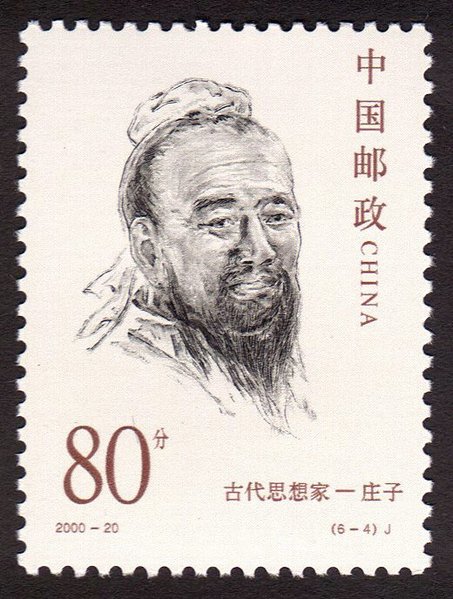

I'm reading Zhuangzi with my class. Always a pleasure, Zhuangzi. Always a challenge, a joy.

The second chapter is one of the most striking expositions of a radical epistemological skepticism that I know (and I admit my knowledge here is limited). Here's this from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

to one correspondence between words and the objects to which they refer

that is an offshoot of the Confucian doctrine of the rectification of

names. He demonstrates that naming is purely arbitrary and conventional

and cannot be used to give any objective certainty about the world.

Furthermore no matter how sophisticated the logic involved, no argument

can establish objective truths because all knowing remains confined to

the standpoint of the knower…

Language and logic are inadequate to the task of understanding. Wow. Without language and logic how then is any understanding possible? Zhuangzi answers this, I believe. with the Cook Ding story: through acute awareness of our immediate surroundings and constant practice of certain appropriate actions in context we can come to "understand," in a sense, through direct experience, a narrow slice of time-space. That's about it. We cannot express that understanding in words, we cannot analyze it logically, we can only apprehend it and enact it. That's what Zhuangzi is getting at in this passage from chapter 2 (Hinton translation):

A sage inquires into realms beyond time and space, but never talks about them. A sage talks about realms within time and space, but never explains. In the Spring and Autumn Annals, where it tells about the ancient emperors, it says the sage explains but never divides. Hence, in difference there's no difference, and in division there's no division. You may ask how this can be. The sage embraces it all. Everyone else divides things, and uses one to reveal the other. Therefore, I say: "Those who divide things cannot see." (27)

For some questions, language is utterly useless; thus the sage (one who has attained Zhuangist understanding) "never talks about them." For other questions, language might be possible, though always imperfect, but analysis is always more of a distortion than a help; thus the sage "never divides." Indeed, emphasis is added to this latter point: "Those who divide things cannot see." Understanding, then, would seem to rely upon seeing things whole, not breaking them down into component parts because in doing so we inevitably create categories and distinctions that are inventions of our own mind, not true to the complexity and dynamism of the ever-unfolding reality of Way. Burton Watson's translation of the last couple of lines cited above may help illuminate this point:

So [I say,] those who divide fail to divide; those who discriminate fail to discriminate. What does this mean, you ask? The sage embraces things. Ordinary men discriminate among them and parade their discriminations before others. So I say, those who discriminate fail to see.

Division and discrimination – analysis – cannot help but fail. When we rely on analysis, we always miss something. A.C. Graham's translation of these same lines gets at this sense of always missing something:

To 'divide', then, is to leave something undivided: to 'discriminate between alternatives' is to leave something which is neither alternative. 'What?' you ask. The sage keeps it in his breast, common men argue over alternatives to show it to each other. Hence I say: 'To "discriminate between alternatives" is to fail to see something'.

Analysis, argumentation, discrimination always leaves something out, always produces partial and faulty and distorted "understanding."

So, Zhuangzi is asking us to give up our reliance on logic and analysis and language in order to move toward a fuller understanding, unfettered by humanly-created categories and discriminations that obstruct our experience of Way.

Can we do it?

UPDATE: Thanks to the Chinese Text Project, here is the Chinese for the key lines variously translated above:

故分也者,有不分也;辩也者,有不辩也。曰:何也?圣人怀之,众人辩之以相示也。故曰:辩也者,有不见也。

Leave a reply to Allan Lian Cancel reply