A piece in Caixin about a questionable qigong "master," brings up a larger point, one that provides some insight into China's current cultural climate. In considering why successful business people and government cadres seek out spiritual guidance from questionable sources, the writer turns to public intellectual Lei Yi:

Lei Yi, a historian at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, says that

this is due to a sense of insecurity troubling China's political and

business elite. They hope to receive some sort of blessing and turn to

these "experts" for career advice and luck.

…

Lei said that superstition is common in all walks of life, but this

"man of God" phenomenon among senior officials and businessmen is worth

special attention. While the worship by entertainers can be written off

as a hobby with little public influence, in the case of officials it

reflects a paradox because they are the ones openly preaching and

advocating materialism and atheism. These words diverge radically from

their thinking, Lei said.

Ultimately, Lei said, this phenomenon showed that "this is an era of lost faith."

This is not at all a novel observation, but it is a useful reminder. The roots of contemporary China's "crisis of faith" go back to the failures of Maoism. For two decades, (roughly 1958-1978) Chinese people had to suppress their anger and frustration with, first, the mass state-sponsored starvation of the Great Leap Famine, and, then, the lethal political insanities of the Cultural Revolution. Deng Xiaoping was smart enough to recognize that Maoism had to be jettisoned, at least in the economic and social realms, if people were once again going to believe in something larger than themselves.

But the strategy of economic reform has turned out only to be half right. It has certainly revived the country materially and kept the CCP afloat politically, but it has not provided a basis of popular faith in broader civic or spiritual principles. Indeed, this same point is the first premise of Jiang Qing's (and others) assertion that Confucianism needs to be remade into something like a state religion, a project that I suspect Lei Yi would reject. (Here is an article – pdf – that provides some historical background on attempts to make Confucianism into a "religion.")

The intellectual and social anxieties mentioned by Lei are more than simply a "lost faith." Business and political and social actors in China seek some sort of transcendent affirmation, but many of them are also search for a transcendent affirmation that is somehow uniquely "Chinese". The "crisis of faith" is bound up with the crisis of contemporary Chinese identity. Or so it seems to me…

But let's stop for a moment and, instead of analyzing the "crisis of faith," think more about what kinds of beliefs are possible in the world today.

I will throw out an assertion that, perhaps, not everyone will accept (critiques welcome!): it is simply not possible to construct a set of transcendent principles that will "unify" or "represent" populations at the scale of the "Chinese people".

If we have learned anything about the dynamics of postmodernity, it is that such efforts, these days (and maybe always in history?) will inevitably descend into authoritarian repression of actually existing intellectual and religious diversity. There simply cannot be "one, holy, catholic, and apostolic" church. There are many and they do not share the same beliefs. Of course, there can be many communities of believers but these communities are always limited, never universal, and they never scale up to truly fill "national" categories. Not all English are believers in the Church of England. Not all Iranians share a single faith community. Globalized postmodernity powerfully reproduces diversity in belief. There's just no escaping that fact of contemporary life.

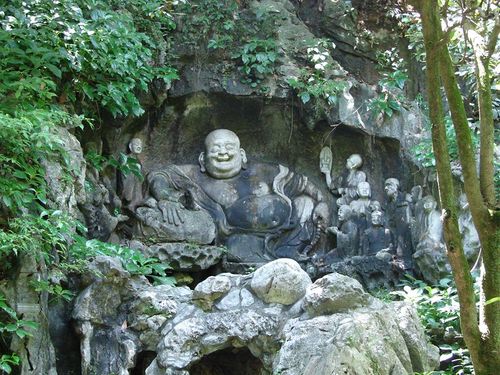

If that is true, then how can there really be a Chinese "crisis of faith"? When I wander about China I see many kinds of believers: Buddhists, Daoists, Christians, secular traditionalists, confirmed and secure atheists, and, yes, Confucians. Zhang Xin is Baha'i. There are all sorts of possibilities. What is missing is a singular or uniform template of faith. But such a thing is really not possible in China or anywhere now.

So, maybe the qigong thing is not a sign of "an era of lost faith" but just the opposite: an era of dynamic finding of faith. Some people will make some strange choices as they search for meaning within postmodernity (I'm more of an Daoist immanentist than a transcendentalist myself…), We still have snake handlers in the US. But so what? It is a shame that some people will get hurt or do stupid things as they search for meaning, but that is their choice. As long as they are not hurting others or causing signficant negative social effects, they should be given some leeway to make mistakes.

And eventually, the silliness of the claims of those qigong "masters" will out.

Bottom line: the "crisis of faith" may only be a "crisis" for those who want to impose a particular faith on a broad population of people. For everyone else, it is an era of freedom to find one's own faith.

Leave a reply to Ngok Ming Cheung Cancel reply