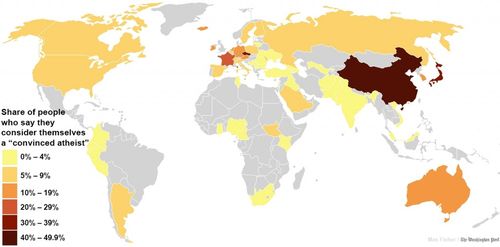

A map popped up in the Washington Post last week, illustrating a recent report (pdf) on expressions of religiosity and atheism around the world. It seems China has the greatest share of the global population of self-identified atheists. And this raises a question: why is China so atheistic?

The Wapo article mentions the Taiping rebellion, a religiously-inspired 19th century civil war that led subsequent Chinese governments to take a dim view of strongly institutionalized faith communities, and the militant atheism of the Maoist regime as key factors in understanding the current situation. These are certainly part of the story. But there are deeper historical-political roots to contemporary atheism in China.

We have to go all the way back to the emergence of a strong, centralized state apparatus and the use of Confucianism as an officially sanctioned state ideology to see the most fundamental origins of atheism in China. This started in the Han dynasty but was refined in the Sui and Tang and after. In essence, the examination system created a powerful incentive for the study and mastery of a particular philosophy. While it it true that there were always other schools of thought and religions circulating in Chinese society – Daoism, Buddhism, Islam, etc. – none of these brought the promise of access to power and wealth in the manner of Confucianism. Fathers would press their sons to learn the Confucian canon and sit for the imperial exams because that was a direct and concrete means to familial prosperity.

The political advantage enjoyed by Confucianism thus privileged a moral theory that did not focus on a god or gods as central figures of worship and meaning. As I have argued before here, Confucianism does not fit neatly into our usual definitions of "religion" because of its "this worldly" orientation. Anna Sun's new book, Confucianism as a World Religion is an extended treatment of the checkered historical interactions of the largely Western-determined definition of "religion" and the Chinese experience of "Confucianism."

As good as Sun's work is, however, I think that the issue here more than a cross-cultural mismatch of sociological categories (i.e. what counts as a "religion" or not). Confucianism simply does not foreground god/gods. It might function as a "religion" in certain ways, but it does not create a universalizing, transcendent faith, in the manner that we usually associate with "religion". Thus, while Confucianism certainly assumes a spirit world, it does not produce a strong theism. We might see it as agnostic. As such, it does not produce a cultural milieu that is strongly supportive of theistic worship. In this negative sense, then, it could be seen as enabling atheism because it does not uphold theism.

Long story short: the material advantages associated with the study of Confucianism within the examination system produced a powerful cultural tendency that facilitated a modern atheism. When the tumult of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries then roiled Chinese society, it is not too surprising that the ultimate result looks like the reported contemporary incidence of atheism. The cultural ground, at least at the elite level of socio-political power, was never all that supportive of theism, and thus atheism faced fewer obstacles.

Of course all of this must be qualified: even though on this one measure China may appear to be the "world's most atheistic country," it is also true that religious faith and practice are growing markedly there. I suspect that Anna Sun would say we are still asking the wrong questions. And she may well be right.

Leave a reply to Sam Cancel reply