A random confluence….

I am running a group independent study in connection with my Nationalism in East Asia class. Three students could not fit the class into their schedules; so we work off the syllabus and meet once a week to discuss various topics. They have read the sources I have mentioned here below: Ernst Gellner, Liah Greenfeld, Benedict Anderson.

In comparing Gellner and Greenfeld, we were mapping out the very different perspectives they take. Gellner is all trans-historical objectivism, arguing that the logic and power of modern industrialization creates an impersonal demand or need for a homogenization of culture at a scale larger than that found in agrarian society and, thus, nationalism is born. It hardly matters what particular definition any specific national identity assumes; something like national identity is simply historically necessary. Greenfeld, by contrast, is all contingent subjectivity. "Nation" is created by a particular social group at a particular historical moment in a particular cultural and linguistic milieu. Its definition as a "sovereign people" precedes what we usually consider modernization, and, pace Gellner, she argues that nationalism produces modernity, not the other way round. Although, once created, it goes on to spread around the world, it was not historically destined to arise and dominate. The world could have turned out differently, something that Gellner would seem to reject.

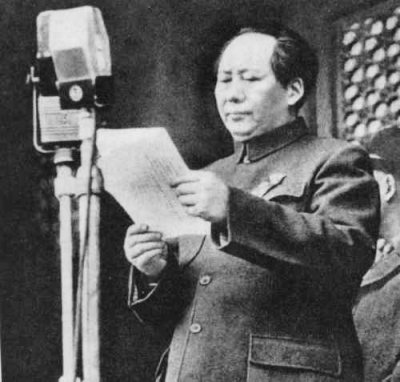

In any event, we were reviewing these points of difference and one of my students looked up and said: "Greenfeld is like Mao."

Wow.

I had worked with this student on Maoist ideology last semester a bit. And I had presented and discussed Maoism with my class then, too. But I had never thought to make this connection. What did she mean?

It is all about subjectivity and, in a sense, creativity. In more orthodox, non-Maoist, strains of Marxism materialism matters. Social and cultural and political change are driven by transformations in the mode of production. More particularly, as Deng Xiaoping emphasized after the passing of Mao, the forces of production (i.e. the productive and technological capacities of the economy) are key. If the economy is poor and underdeveloped, that will shape the politics, culture and society. Mao fundamentally rejected this view – to horrible effect during the Great Leap Forward. He was impatient with a stricter materialism (which suggested that China could not reach "socialism" or "communism" for many decades) and he emphasized the relations of production: the social organization and motivations of people. Indeed, he went further and embraced a voluntarism that asserted the sheer will of the people could hasten material progress. Millions and millions of people died as a result of his fatal detachment from a more realistic materialism.

My student was not suggesting that Greenfeld was a Maoist in any political sense. Rather, If Maoism focuses on the creative (and destructive) potential of willful human agents in history, who can construct "objective" facts on the ground, then Greenfeld shares, to a degree, that point of view. She does not view nationalism as the ineluctable outcome of the material and structural transformations of industrialization, as does Gellner (who somewhat ironically works hard to try to distance himself from Marxism). Rather, she sees nationalism as the invention of determined and willful and creative agents in a particular historical context. In that way, Greenfeld is like Mao…

OK, I don't expect any of you out there to really get a kick out of this. It is just a peculiar crossing of two strains of thought that I had never seen crossed or thought of crossing. A random confluence.

For a reminiscence on his biography of Mao, with some insights into the publishing industry in the PRC, this post today by Ross Terrill over at The China Beat is instructive….

Mao is strangely in the air this week….

Leave a reply to stevelaudig Cancel reply