A story in The Global Times reports on the enactment of an amendment to the PRC Law on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly that requires adult children to visit their elderly parents. This has been in the works for a while, and has been criticized within China, but the new rule has come into force nonetheless.

It strikes me as a bad idea. Most children want to visit their parents, but circumstances often get in the way. That can be sad, even tragic, at times, especially for lonely parents, but forcing, by act of law, family gatherings will likely create resentment, and undermine relationships. Simply counterproductive.

China, like everywhere else on the planet, is caught between the impersonal pressures of modernization and the image of traditional society. There is a sense of loss, perhaps based on an idealized notion of the past, but a significant feeling nonetheless. The article points to the economic forces that split families apart:

A survey found that 77 percent of some 10,000 respondents said they

visit their parents only once every six months, with 36 percent of

migrant workers seeing their folks only once a year, mainly during

China's Spring Festival period, Xinhua News Agency reported.

"It's

not that I don't want to go home but I really don't have time," Tang

Xiaohua, who hails from Guangdong Province but works in Beijing, told

the Global Times.

He wants to move his parents to the big city,

but he worries they would not fit in there. Even if his parents agreed

to live with him, he probably could not afford it, Tang explains.

He needs to find a job, and that sends him into cities, away from his parents. It's hard to carve out the time, from the highly competitive job market, to go to see them. He'd like to move them to the city but he can't afford it. Hard to see how a legally enforced visit home solves any of the larger forces at work.

The article notes both the problems that have inspired the new law, and the fears about what it will produce:

Many lawyers and professors criticized the amendment, saying turning Confucian values into law would push society backward.

"Admittedly,

the lack of filial respect has become an issue in recent years, but the

reason behind it is our education," said Zhao. "We focus too much on

how to get ahead instead of being respectful to the elderly."

But

despite the protests, it is now official. Many adult children said they

do not feel comfortable about being forced to visit their parents.

Simply put, China is not a Confucian society. The modernized economy and society and culture create incentives and demands that undermine older notions of filial duty. I would not blame "education." It's much more than that. Although it might be possible to find ways to do better, in a modern context, by way of caring for the elderly, it is impossible to live up to a Confucian standard of such care.

What is a Confucian standard? My sense is that Confucianism would require us to resolve any family v. work tension in favor of the family. If a child had to give up a good job to move back to the village to take care of parents, then that is what should be done. It is better to be poor and virtuous than to be rich and unfilial. But that idea has less purchase in China today.

And if traditional moral sensibilities have eroded, they cannot be recreated through law. Confucius understood this:

When Adept Yu asked about honoring parents, the Master said: "These days, being a worthy child just means keeping parents well-fed. That's what we do for dogs and horses. Everyone can feed their parents – but without reverence, they might as well be feeding animals. (2.7)

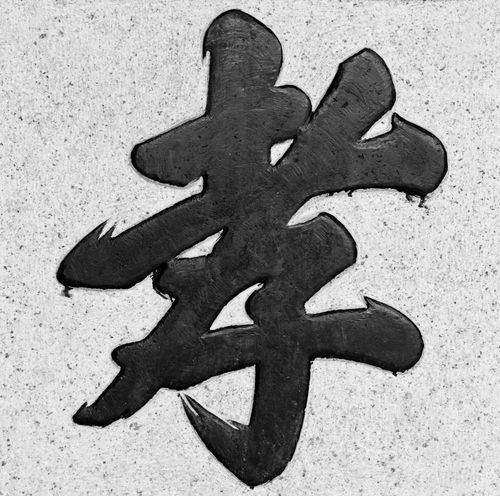

子游問孝。子曰:「今之孝者,是謂能養。至於犬馬,皆能有養;不敬,何以別乎?」

It's not about law, it's about "reverence" (敬)

Leave a comment