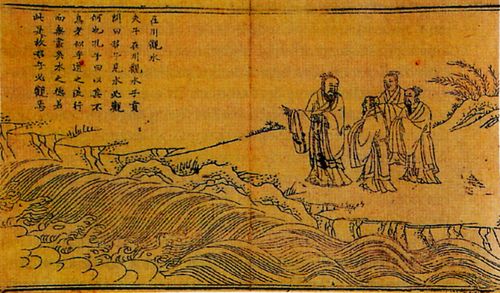

My recent post on how a Confucian might understand the corruption surrounding Wen Jiabao sparked a couple of comments that have pushed me to think a bit more about the topic. But I am thinking more broadly about both Confucianism and corruption in China.

One comment, a rather knee-jerk rejection of my interpretation of Confucianism in this case, suggests that an overly stringent application of Confucian principles is useless:

But if

such a "standard" is followed by politicians, there would essentially be

no one working in government. Anywhere. Anytime. Even the best among

human beings would be self-excluded from government office. Your

inability to draw that implication is ghastly.

What strikes me immediately about this response is that it is, essentially, the same argument made by Han Feizi, the prominent Legalist writer (here's a pdf of an article on Han's critique of Confucianism). In the book that bears his name, Han places Confucians among what he refers to as the "five vermin." Not pulling any punches there. Han says:

Confucius was one of the greatest sages of the world. He perfected his conduct, made clear the Way, and traveled throughout the area within the four seas, but in all that area those who rejoiced in his benevolence, admired his righteousness, and were willing to become his disciples numbered only seventy. For to honor benevolence is a rare thing, and to adhere to righteousness is hard. Therefore, within the vast area of the world only seventy men became his disciples, and only one man – himself – was truly benevolent and righteous. (102)

He emphasizes the number seventy because it illustrates how unrealistic Confucian expectations are. Only seventy people seriously followed those principles, and that is clearly an insufficient number of administrators to manage the affairs of one medium-sized state, much less provide a more universal political guide. Legalists, in short, reject Confucianism as being hopelessly idealistic and optimistic about human behavior.

Contemporary invocations of the Legalist rejection of Confucianism (whether they are intentional or not) raise the question (again, whether it is intended or not) of whether China is, or really ever has been, a "Confucian society." For over two thousand years some Chinese people (Legalists, Mohists) have argued that Confucianism is a highfalutin ideal that does not reflect how life is really lived in China. I think there is some truth in that statement. But, unlike Legalists, I still believe that Confucianism can still function as a moral standard. Perhaps it sets a very high bar, one that few of us, realistically, can reach. Yet the point of such an exceptional benchmark is to inspire us to always try to do better in our moral lives. We may never attain the full measure of Confucian morality, but we can continue to work to do better than before. (In a way, we can see a similarity here in the person of Jesus. Few of us would say we truly live as Jesus would have us live, but, still, we can strive to live up to that standard as best we can. And, no, I do not mean to suggest in this analogy that Confucianism is just like Christianity; it's not….).

An irony here is that some – nationalists and fenqing – who might want to reject Confucianism (on essentially Legalist grounds) as impractical, also want to hold on to it as an element of tradition that distinguishes Chinese experience from the West. Confucianism is thus used to assert a kind of Chinese exceptionalism that ultimately rejects that actual application of Confucian standards. In a sense, they want to have their Confucian cake and not eat it.

In any event, I would assert that Confucianism can be invoked as a contemporary moral standard, not just in China but in other non-Chinese contexts. (I better believe it since I just wrote a book that does just that…). Impracticality is not an end to ethical debate. It may be difficult to do the right thing, but difficulty does not make the right thing less right.

So, the next general question is: what would Confucius do (WWCD)? What would he do when confronted with the kind of corruption that the Wen Jiabao case and so many other cases demonstrate? The more specific question here is: is it wrong for family members to unfairly profit from a person's official position? "Unfairly profit" denotes the various hidden-from-the-public techniques that are used to amass wealth based on proximity of positions of power (guanxi in common parlance) and not true merit or hard work.

We should first point out that Wen Jiabao himself believes that such unfair profit is wrong. In March in a news conference at the end of the National People's Congress session, he pointedly called out "… increases in corruption and income disparity and a decline in the government’s credibility." And the Chinese Communist Party has rules that forbid the kind of activity Wen's family members allegedly have undertaken.

But would a Confucian (I do not assume that Wen is a Confucian or motivated by Confucian values) have the same view? Yes. At least we can come to that conclusion based on the texts of the Analects and Mencius.

For Confucius, officials should not be thinking about material gain:

The Master said: "The noble-minded devote themselves to the Way, not to earning a living. A farmer may go hungry, and a scholar may stumble into a good salary. So it is that the noble-minded worry about the Way, not poverty and hunger. (Analects, Hinton, 15.31; other translations have this as 15.32)

"Way" (Dao) for Confucius is all about doing the right thing, enacting duty according to ritual to move toward humanity. And he is clear: "noble-minded" people – and officials at all levels should strive to be noble-minded – should worry about doing the right thing, they should not worry about poverty. Indeed, the Chinese phrase could serve as a guiding motto for corruption-fighting in the PRC today:

君子憂道不憂貧

Mencius, as usual, is more dramatic in making the same point. When confronting Emperor Hui of Liang, who lives an extravagant life in the midst of poverty and inequality, he argues:

"There's plenty of juicy meat in your kitchen and plenty of well-fed horses in your stable," continued Mencius, "but the people here look hungry, and in the countryside they're starving to death. You're feeding humans to animals. Everyone hates to see animals eat each other, and an emperor is the people's father and mother – but if his government feeds humans to animals, how can he claim to be the people's father and mother? (Hinton, 1.4)

The contemporary analogues here might be meals at five star restaurants and Ferrari's in the garage. The point is that leaders should not be feathering their own nests when there are people in their country that do not have sufficient material means to carry out their familial duties with requisite dignity. And that is something that certainly applies to the PRC today.

What action should an official take if he or she discovers malfeasance in high places? Speaking up and bearing witness and calling out the wrongdoers is certainly appropriate; indeed, that pretty much sums up Mencius's life. But if things are bad and not getting better, a person in an official position should be willing to walk away from that position, to resign and thus call further attention to the venality. Analects 18.4 suggests that Confucius himself did just that:

The men of Qi presented [the government of] Lu with a troupe of women musicians. Ji Huanzi accepted them and for three days failed to appear at court. Confucius left the state. (Watson)

On the face of it, Confucius here witnesses improper behavior – the women musicians are obviously an indulgence meant to distract the leaders of Qi from doing their public duty – and resigns his office as a result. Further study, such as that by Annping Chin (chapter 1), reveals that this situation might have been a bit more complex. But the writers of the Analects want us to understand this episode as a matter of righteous resignation. That is what a leader who is trying to live up to a Confucian moral standard would do.

And that is what Wen Jiabao should do, or should have done, if he truly cares about the kind of corruption he says he cares about. My interlocutor is having none of this, however:

To

think that by resigning on account of family members' getting rich would

make his country better or reduce corruption is baseless.

It seems that the only reason for such a move is a kind of empty gesture.

In Confucian terms it would hardly be "baseless," since Confucius himself took this course of action. But would it be simply an "empty gesture"? It is likely that a Wen resignation would not structurally transform the PRC political economy, not in the near-term at least. Yet, again from a Confucian point of view, certain actions ought to be taken regardless of our initial calculation of their political effectiveness. Moreover, the Confucian belief in exemplary moral leadership would invest much more importance in a Wen resignation. It would be an extraordinary thing. Unprecedented, really. And thus it would bring much, much greater attention to the problem of high-level corruption. Perhaps it would spark some sort of longer term political change. That, at least, is the belief of Confucius when he says in Analects 12.19:

The noble-minded have the integrity of wind, and the little people the integrity of grass. When the wind sweeps over the grass it bends.

The actions of leaders like Wen Jiabao should be so movingly ethical that people will naturally follow, a moral charisma of sorts that sweeps everyone along. That is what they should be but, alas, they are not, because Wen either does not care to do anything truly remarkable to counteract corruption or he lacks the courage to do so.

Another commenter raises an interesting point:

The

question for me is whether he has try to set China in the right

direction and benefitted the people overall. I think he succeeded to

certain extent and leave it for his successor to further reform and

transparency. He is a politician and constrained by history, and history

will judge him. I do wish him well in his retirement.

This has a bit of a Mencian ring to it: a leader should be judged by how well he improves the material well-being of the people. Wen has overseen rapid economic growth and, as is often stated, many, many Chinese people have risen out of absolute poverty as a result. Those are good and laudable things. But, I think a further Mencian consideration would be inequality. How many people are being left behind? How many have not benefited sufficiently from the booming economy? If we believe that more effort needs to be undertaken to attend to the poor and disadvantaged, and that on-going high-level corruption distracts from that important work, then there would still be Confucian grounds for a Wen resignation. Personally, I believe that that is the case and if Wen wanted to do the right Confucian thing he would resign.

Ultimately, however, I do not think Wen will resign. He does not hold that strongly to a Confucian morality. But that does not mean we cannot use that morality to judge his actions, or the actions of others, like Mitt Romney, or whomever. Whether or not "Confucianism" exists in China or America or anywhere else is immaterial to the application of Confucian standards to the behavior of political leaders.

Leave a comment