That's the title of a piece in The Global Times a couple of days ago, reporting on a class, held under the auspices of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, in which Chinese Christians read The Analects and contemplate parallels between Confucianism and Christianity. Intellectually, this could be an interesting conversation, but, politically, I wonder if it is an effort to centrally control the definition of "Chinese culture."

The intellectual project leads quite naturally to certain similarities between the two faiths (as I have written before that I do not generally view Confucianism as a religion but it might be a "faith" or sorts). The golden rule and all that. But I would hesitate to accept this line of thought:

"We believe there are similarities between the Analects and the Bible, but Confucius didn't express such thoughts thoroughly," said Shi. He believes that by talking about proper timing for everything, Confucius was in essence talking about following the will of God or Heaven. "We believe that Confucius, like all other human beings, was instinctively pursuing God, or a higher power, and looking for the ultimate answers," he [Shi Hengtan from CASS] added.

I don't think Confucius was talking about following the will of God. Tian, Heaven, doesn't quite function like a God or gods. It is too diffuse. It is not really a place of redemption. The article goes on to state that most scholars of Confucianism in China would reject this idea. Of course, most of them, as well as myself, are not attempting a Christian reading of the texts. Maybe that is how we should leave it: if you look for God in Confucianism you may find it, but that doesn't mean it has to be there, nor that that is the understanding that Confucius and his early disciples held.

Politically, the article made me think of the desire to centrally control culture. That desire runs deep in imperial China, when state power was linked to cultural orthodoxy. And it was certainly a key feature of Maoist China, when socialist apparatchiks enforced a bland and narrow socialist-realism in place of the old state-Confucianism. The post-Mao period has seen a much greater degree of cultural freedom, and a subsequent efflorescence of religious belief and practice. But the desire for centralized political control of culture remains, and is perhaps getting stronger as the society becomes more culturally diverse.

Thus, the fact that it is CASS, a branch of the state, that is organizing these classes raises a question of motivation. I am willing to take Shi Hengtan at his word when he says the main purpose here "is to help Christians learn and understand traditional Chinese culture." But then there is this idea:

"Christianity in China has yet to be better integrated into Chinese culture, and that's what we are trying to do," said Shi.

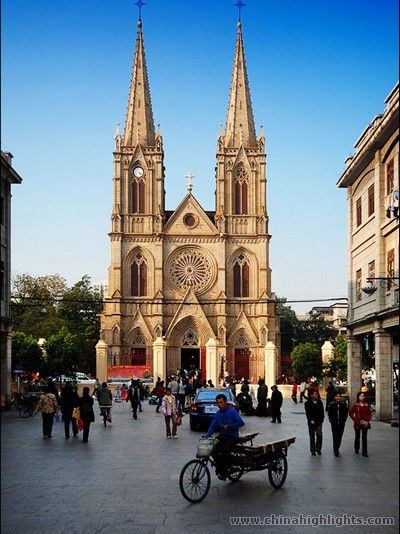

What is meant by "integration"? I imagine Chinese nationalists will be uncomfortable with this insofar as they see Christianity as an alien, Western force aimed at subjugating China. I see the issue rather differently, starting with the question of what is "Chinese culture"? I think we should take a broad view of that concept, recognizing the many different sources and strands of culture that have emerged in and moved through China over the centuries. Thus, at this point in history, I think we should not make a distinction between "Christianity" and "Chinese culture." Christianity has been in China for centuries and has been absorbed into "Chinese culture," just like Buddhism before it. Yes, Buddhism has had a more extensive cultural presence in China but it came from elsewhere and was adapted over time. Similarly, "Islam" is a part of Chinese culture. Chinese muslims should not be considered as somehow outside of "Chinese culture."

If thought of that way, there really is no need to integrate Christianity into Chinese culture, especially no need for such a project to be carried out through the agency of the state. But the state, and ultimately the Party, wants to control the definition and development of "Chinese culture." State agents take it as their duty to orchestrate cultural production and expression in a manner that serves state interests. Cultural heterodoxy is a poltiical problem.

It should be noted that this impulse to control culture is by no means peculiar to China. We see it in the axieties of American conservatives bewailing the decline of "American culture."

But centralized political resistance to cultural change is more pronounced in the PRC because there are fewer formal limits on state power.

So, let Christians read Confucius, and let Confucians read the Bible, and everyone should read Zhaungzi. It's a big, wide globalized cultural world out there that can be approached and experienced in myriad ways. Trying to hold on to static definitions of "Chinese" or "American" culture is intellectually stultifying and, ultimately, futile.

Leave a comment