I had a great day yesterday. A very engaging and productive time at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. Some good responses to my presentation on Confucianism and soft power, and even better, broad-ranging conversation afterward. Much to think about and absorb and, eventually, blog. In the evening I had a fun time with a diverse gathering of journalists and others at the Foreign Correspondent's Club here. My talk to them was a bit different that the more academic presentation that morning, and I was able to float a variety of ideas to an informed audience. And the martinis later with a couple of former students in a bar in the mansion that had been the home of a Shanghai gangster was a great way to cap the last night in Shanghai.

Throughout my short time here, one of the ideas I have been raising is that China is not now a Confucian society. This notion has been met with mixed responses here. Some Chinese, scholars and students alike, agree that modernization has transformed China to such an extent that it is very difficult to say that consistent Confucian behavior is common here (and by "Confucianism" I mean a rigorous moral practice). Materialist instrumentalism (or instrumental materialism) is just too powerful an economic and social dynamic to maintain the humanist sociality of Confucianism. That's not to say there are no traces or expressions of Confucian-like intentions and actions, there are. But they do not sufficiently add up at the level of society and economy to justify calling this place a "Confucian society."

I obviously need to refine and hone this argument. And I will be aided in that endeavor by the points made by those here who have disagreed with me. Negative responses came from students and scholars and they were offered with varying degrees of fervency. One Chinese student at Beijing Foreign Studies University was quite direct and comprehensive in her rejection of my suggestion that China is not a Confucian society. I believe that I can rebut most of her points, and I will be thinking through them in the next few days, but here I want to step back and think about a larger issue.

Why do some Chinese very much want to believe that China is a Confucian society? What's at stake in that conception?

Various people here mentioned the familiar point that China is facing a crisis of faith or a vacuum of principles. The very rapid and extensive economic and social and cultural change is destabalizing. Personal and collective identites are called into question. And in that context, reaching for some grounding in cultural distinctiveness and historical continuity can provide some comfort and confidence.

I think this is generally true. But I don't think this is a particularly Chinese phenomenon. All countries and cultures that face globalized modernity face the same problem. In the US, the "culture wars" are essentially the same thing: people debating what it means to be "American" in the face of continual and fundamental social and cultural change. It is generally the more conservative resopnse to change that reaches for cultural distsinctiveness (which in the US takes the form of American excetionalism) and historical continuity. That what conservatism means: to conserve something essential about social organization and cultural identity.

What is unique about China now is the speed and extent of change. Everything is moving faster here, faster than the US, faster than many people feel comfortable with. And perhaps that is why the conservative response, which here includes the neo-traditionalist re-invention of Confucianism, is so prominent in certain quarters. But, however dizzying the pace of change here, I don't think that the yearning for cultral distinctiveness and historical continuity is all that different from the cultural dynamics of the US.

Paradoxically, the two countries may be more alike than either might realize, and their similarity lies in their efforts to define and conserve cultural difference in a world of inescapable change…. We all look to assert what is culturally distinctive about our place in that world, and the historical continuities that link us to the past of our place in the world…

Something to think about as I face a twelve hour flight back to the US, and then another short flight and car ride home.

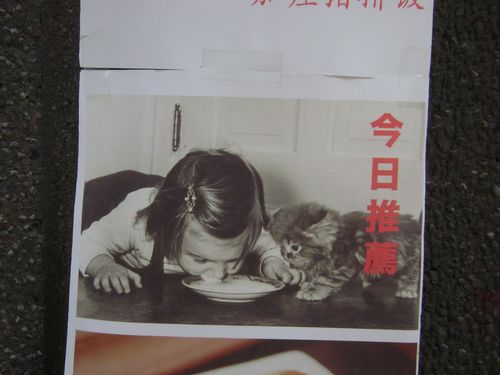

In the meantime, here's a funny post card from Tai Kung lu; the caption reads something like: "today's recommendation" or, maybe "recommended daily."

Leave a comment